PROLEGOMENON TOWARDS VOIDWAVE #1: THE HEAD CANON AND THE LONG 1970s

LOU REED, IAN CURTIS AND THE SEVENTIES ROMANCE OF DESPAIR

BY JON KROMKA

‘Love is but a song we sing, fear’s the way we die’. The opening lines of Chet Powers’ peace anthem ‘Get Together’, unfolding in the diaphanous jangle of the Youngbloods’ 1967 version, conjures an ambiguous mood that some of us who were children of the 1970s remember as a prevailing climate. A stark dialectic is set forward in those lines that colours the rest of the song, undermining its rousing chorus, exposing it as a feeble plea to sustain a (largely imagined) state of grace that was already slipping through everyone’s fingers. It’s something felt better by us 70s kids than we were capable of understanding shifting social attitudes as countercultural moral imperatives turned into New Age platitudes and, by the punk era, despised hippie clichés. That’s why a historical overview such as Francis Wheen’s Strange Days Indeed only tells half the story. By framing the decade’s collective ‘style’ as paranoid, he pursues an interpretive strategy that plays into a conventional media narrative: the counterculture’s utopian aspirations rendered as ephemeral as marijuana haze; the decade as the jittery, manic comedown from the sixties love-ins. There’s an element of comedy to paranoia, fewer associations of levity with melancholia. A perceivable trace endures in 70s culture: the half-life of stifled dreams turned sour but still emitting radiation. Paranoia’s definitely a part of the mix; as Wheen rightly observes the era is defined by an all-pervasive distrust between left and right, then as now. But there’s also an aesthetic quality not so much of romantic despair, but a romance of despair: an ongoing process – seductive and vortical – that has not yet finished in some quarters, visible in the persistence of certain tropes and iconography amid shifting trends and evolving practices.

Sufferers’ concerns in this depressive decade were more metaphysical than allowed for in pathological diagnosis. Of all the forms of anti-psychiatry to emerge from the sixties, the most metaphysical was schizoanalysis. Its inventors, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, borrowed as much from surrealist conceptualists like Antonin Artaud and philosophers like Nietzsche and Spinoza as they did, critically, from Sigmund Freud to write their anti-fascist manual Anti-Oedipus (1972). They aimed to free the unconscious from the moribund classical theatre of the Oedipal triangle and restore its true function as a producer of desire. A milieu is described, a zone between reality and fantasy, in which semiotic constructs called assemblages have material force beyond mere representation. Schizophrenia is given a special political meaning: a process of becoming, a new way of being, rather than a condition. Taking inspiration from the events of May ’68, the work resonated with the aims of a youth movement that sought to break desire out of the prison of family structures, to give it sovereignty to transform social, political and economic institutions. The philosopher (Deleuze) and the activist-psychotherapist (Guattari) describe a social delirium emerging from capitalism’s inherent contradictions: it frees desires from archaic structures, only to repress them again with codes – commercial, political, religious, legal, scientific. The delirium has polarity, switching between ‘paranoiac-segregative’ and ‘schizonomadic’ modes, the unconscious oscillating between the ‘reactionary charge and its revolutionary potential.’ Terms like deterritorialization and reterritorialization describe the processes by which desire can take a line of flight through a milieu, to forge a path of becoming, or fall prey to an apparatus of capture, turning the revolutionary into the counter-revolutionary.

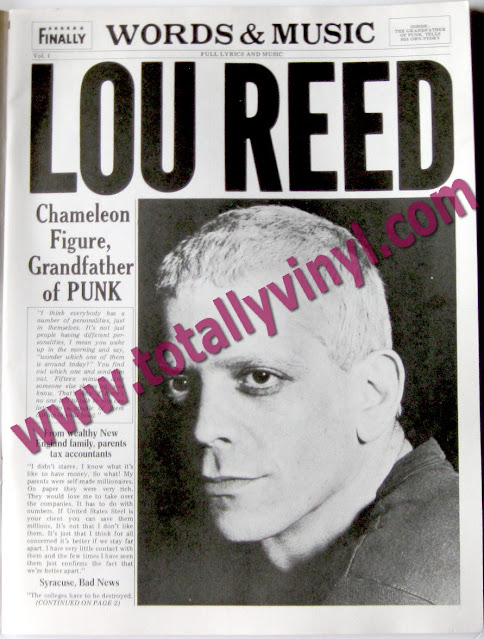

The dynamics of this bipolar unconscious infiltrate the cultural expression of a decade that began with the gradual dissolution of revolutionary activity, and ended with a strengthened hegemony built on neoliberal capitalism and conservative principles. Newly won social freedoms were explored and cultural experimentation took place within a milieu of stagflation (as of 2021, projected to return by some economists as the disruption caused by the pandemic continues), political corruption and the emergence of modern terrorism (as of 2021, mutating into the conspiratorial vortex of QAnon). A utopian impulse, the dying embers of sixties idealism, burned in popular culture for a time even as it was gradually lost in co-opted tropes: the mystification produced by the convergence of drugs and the occult; cinematic violence on a trajectory of hyperbole that became the visceral overkill of death/black metal and torture porn; the ever diminishing returns of postmodern irony as an end unto itself. Amid a transformation of base and superstructure, a shift from manufacturing to what philosopher Antonio Negri and literary theorist Michael Hardt call immaterial labour, the sign, with all the multivalent spin poststructuralism demonstrated it to possess, acquired greater potential for psychological investment. An artist who recognized the fluid potency of signs for both fashion and political statement, someone who probably hated psychiatrists more than Felix Guattari, was the musician Lou Reed. During perhaps the most delirious stage of his career Reed exerted an influence on young English fans, and one in particular, that’s open to schizoanalytic interpretation.

Anton Corbijn’s biopic Control recreates a moment when Factory label owner Tony Wilson tries to cheer up Joy Division lead singer Ian Curtis after a disastrous show at Bury Derby Hall. A riot had ensued when Curtis’ epileptic seizure brought a premature end to the group’s set. Wilson extols the rebellious cachet of the melee, referring to another infamous rock concert - the Manchester Free Trade Hall gig during Lou Reed’s 'Sally Can't Dance' tour. Curtis hadn’t been at that event, but he’d heard about it, knew enough about it to gasp ‘the riot’ at its mention with reverent awe. Wilson nods in recognition – he and Curtis no longer management and talent, but two Reed fans sharing a moment - and says it was the best concert he ever saw.

Seventeen year-old Ian Curtis saw Reed perform at the Liverpool Empire during the 'Rock and Roll Animal' world tour of 1973/74. Some tours capitalize on an album's success, as the ‘Sally Can’t Dance’ tour followed upon the hit single and album of that name, but the ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal’ tour was an undertaking of financial recovery following the commercial failure of Berlin. That concept album’s grim examination of drug addiction, marital breakdown and suicide proved too depressing for audiences expecting more of the glam celebration of the David Bowie produced Transformer. The heavy rock sound of this tour alienated some fans – attracted more by the light pop arrangements of his hit solo album than the prototypical metal and noise elements of Reed’s original band - as much as Berlin unsettled them. There were a number of riots throughout Europe.

The embryo of Curtis' hypnotic stage persona can be discerned in Australian television footage of the ex-Velvet Underground member performing ‘Rock and Roll’ at Sydney's Hordern Pavilion in 1974. Reed’s paroxysmal dance routine has a similar quality of the shaman-automaton, locked hips and flailing arms inscribing obscure symbols in the air. His trademark look of the time was captured in the alienated cool on the cover shot of his infamous experimental album Metal Machine Music (one of Curtis' favourites): black leather pants, black t-shirt, black shades, black nail varnish adorned the gaunt frame of a speed freak, topped with a peroxide blonde buzz cut into which he had shaved Iron Crosses; or swastikas depending on the witness or the angle.

Like Ian Curtis, Lou Reed conjured a wider and darker context for his St. Vitus dancing: a symbolic gallery that suggests a jive version of Petrushka – the puppet in Stravinsky's ballet, a synecdoche for the manipulation of the individual by historical forces – given flesh only to find himself caught in a web formed from the attributes in Spinoza's iron geometry of necessity. Each twisted movement and gesture, every convergence of shadow and outline, creates a different impression: he is a decadent Weimar-era performer recast as glam hero and concentration camp inmate, Golem and Aryan man-machine. What was the real cause of the riots that often followed these shows? High spirits getting out of hand? Anger over capacity planning or seating arrangements? Reed's refusal to do an encore, as happened at the Manchester Free Trade Hall concert? The oppressive jazz-metal sound? Perhaps something more underneath these surface factors: a delayed collective unconscious reaction to a subliminal atmosphere of paranoia, a mass confrontation with the unfathomable dimensions of the other.

The autocannibalistic brain fever of amphetamine-fuelled insomnia seems to be both inspiration and driving force for Reed’s expression in this period. He confided to members of his entourage that he was afraid to sleep as he had terrible nightmares about himself. Many involved the electro-shock treatment he underwent as a teenager, approved by his parents on a psychiatrist’s recommendation.

What influenced this parental decision: a combination of authoritarian deference and belief in the infallibility of medical experts? A desire to cure their son of any non-conformist tendencies? As middle class Jews, they may have been feeling socially wary in the wake of the Second Red Scare with its targeting of homosexuals and anti-Semitic tone: a political reaction to Trotsky, Jewish prophet of international revolution. Revolt against compromise was part of the agenda for the heroes of the glam and punk movements. But there's sentimentality in a Lou Reed song like 'Rock and Roll', too; bittersweet harmony complements the subtle undercurrent of metallic abrasion in the 'despite all the amputations' section. When five year-old 'Jenny', Reed's anima, calls her parents and the comfortable middle class life they provide the 'death of us all', it sounds more like a child's flippant exaggeration than outright condemnation. The caustic accusation of ‘Kill Your Sons’ is yet to emerge.

The traumatic experience of the electro-shock therapy, whatever the reasons behind it, became a dominant element in Reed's life and art. The physical effects were short-lived, but the betrayal of it affected him emotionally for a much longer period. He has said his real personality was taken from him in that treatment, to be replaced by a succession of shifting simulacra. In his Lou Reed: The Biography, Victor Bockris notes how Lou's adult nightmares, as described in his poetry, were dominated by the 'sad, off-white colour of hospitals'. Following the failure of an album in which he had invested so much artistic energy, touring life had become a routine cycle of performances before fickle fans he was growing to despise; a succession of hotel rooms in which, as Lester Bangs found, he would often spend the night trying to avoid nightmares of youth. “How do you think it feels,” he sang on a song from Berlin, “when you're speeding and lonely?...How do you think it feels?/When you've been up for five days/Hunting around always/'Cause you're afraid of sleeping.”

Ian Curtis, the aspiring rock performer and fan musicologist, would have followed Reed’s story assiduously in music papers; as a regular NME reader, it’s highly likely he would have read Nick Kent’s articles. Like Bangs’, they provide acerbic descriptions of Reed’s latest outrageous look and amphetamine-abusing, insomniac attitude, but with an eloquence that contributes to the romantic decadence of the singer’s proto-punk appeal. As a fan of J.G. Ballard, fascinated by insights into mental disturbance provided by family members employed in the health sector, Curtis may have felt, observing his idol's frenetic, venomous persona on stage, an atmosphere where the science fiction writer’s psychological metaphors for the perils of prolonged consciousness (dislocation, hallucination) complement a youthful appeal in pushing the limits of human energy, of extending the day as well as seizing it (waging the war against sleep, as Einsturzende Neubauten leader Blixa Bargeld was to later put it). Might these impressions have merged with an insight into his own possible future that inspired desire and dread in equal measure?

In his short story 'Manhole 69', Ballard has the scientist Neill conduct a neurosurgical experiment in which the brain is rewired to remove the need, and the capacity, for sleep. Sleep deprivation has been used as a torture technique since the witch trials, but Neill feels it necessary to expand mankind’s quotient of useful, productive time. The result is catatonic withdrawal for the test subjects. Neill’s assistant Morley expresses methodological doubts throughout; concerned about objectives, he questions the wisdom of taking away sleep’s gift to the individual of eight hours a day to “get over the shock of being you”. A conversation between Neill and Morley about the conscious state of their test subjects springs from a discussion of the Anton Chekhov tale, 'The Bet', in which a man accepts a million-rouble bet that he cannot shut himself alone in his room for ten years. Like the man in the room, the subjects have become conscious of nothing else but their own identity, a concept that has slipped its boundaries. The psychotic refashions reality for his own purposes from within this inescapable totality of self-awareness. “The room in Chekhov's story gives me an idea as to how they might have re-adjusted,” Neill explains. “Their particular equivalent of this room was the gym. I'm beginning to realise it was a mistake to put them in there – all those lights blazing down, the huge floor, high walls. They merely exaggerate the sensation of overload. In fact the gym might easily have become an external projection of their own egos.”

The persona that Reed projected from the stage into the enclosed space of performance venues was an amalgam of megalomaniacal rock star, anticipating the totalitarian fantasy sequences of Pink Floyd's The Wall, and the subject of some Kafkaesque existential drama – man metamorphosed into stick insect, stuck on the pin of a spotlight; like Warren Beatty’s persecuted comedian in Arthur Penn’s surrealistic noir Mickey One, trying to answer the obscure judgment of unseen powers with a routine. Reed made the stage environment a projection of his inner dilemma, a shadow play of power and powerlessness. Partly due to budgetary considerations, he used Albert Speer's striking, austere design for Adolf Hitler's speeches to light his European shows. The combination of a black stage and severe, white spotlights made him the centre of illumination within a high contrast frame. As lighting technician Bernie Gelb described it, the audience’s view of the spectacle was restricted to Reed and reflected light. The staging adjustments necessary to accommodate Curtis' epileptic condition would impose a similarly stark lighting arrangement for Joy Division concerts.

In the Sydney Hordern Pavilion footage Reed sings 'Rock and Roll' – in its original version on the Velvet Underground's final album Loaded, a celebration of the liberating effects of music, one of the best pop songs about pop itself – with the hysterical convulsions of a malfunctioning robot. He barks out his lines and then pulls back from the microphone as though in retreat from a host of ghouls he tries to ward off with hexes drawn in the air. Future Joy Division guitarist Bernard Sumner was at the Free Trade Hall concert. He describes in his autobiography Chapter and Verse how a totally out of it Reed continually smashed microphones, like some contradictory attempt to silence his own performance. Like the man in the Chekhov story, Reed had been trapped in the same room for years, a psychological torture chamber like any conceived by Hubert Selby Jnr. A carefully cultivated, psychotic bad boy persona, the rebel role as psychic armour, becomes the rock star as a character from a Poe story: the man who was nowhere, operating from a realm of reflected signifiers, like the blank, static-filled television screens before which he would later perform 'Kicks', projecting a negative joy directed both inwards and outwards. He said he pulled down the blinds against the outside world after Berlin’s commercial failure. External representation of that isolation turned a Warholian celebration of the surface into a Stygian mirror.

The fact that Reed was Jewish made the particular symbols he employed more than blank expressions of nihilistic transgression, like the punks’ adoption of Nazi regalia; something more like embodied inscriptions from a despotic socius. A form of visual protest over the way his career was being handled, a fashion statement originally intended to antagonize manager Dennis Katz, also a protest against the electroshock treatment that was designed to cure him of bisexuality: the brands of state correction on either temporal lobe flowered into authoritarian insignia. Was choosing to wear iron crosses in your hair the sarcastic obverse of being forced to wear the Star of David on your clothes? Reed did not directly address anti-Semitism in song until ‘Good Evening Mr. Waldheim’ on his 1989 album New York, but the obscurity of this earlier symbolic employment, its diachronic/synchronic evocation of a mechanics of bigotry and exclusion, enhanced its subliminal energy. By intention or otherwise, might these signs have drawn his Gentile audiences – especially history obsessive Curtis - into an unconscious chain of sociohistorical libidinal investment in which they were morally implicated?

Anti-Semites, especially those that historian Daniel Jonah Goldhagen says are prone to a form of magical thinking still extant since the Middle Ages, see the object of their hatred as the cause of all their evils. Jean-Paul Sartre argued the concept of the ‘Jew’, as opposed to its lived reality, was itself the creation of anti-Semites. Throughout the course of European history, it was used to trap the enemy in a dialectic between two imposed roles: one, the religious scapegoat - a PR stitch up in the Gospels engineered by the early Christian Church and the Roman imperial state, diminishing the latter's responsibility for the execution of Christ; the other, the royal banker who acquired superior financial acumen because his people was barred from most other professions and Christians were forbidden to engage in money lending. Cultural antagonism re-emerged during the Depression years, the inescapable transition of Weimar into Third Reich, conjured by Reed with those crosses mutating into swastikas on his branded skull. Goldhagen’s examination of historical records indicates that many interbellum Germans felt doubly, delusionally, justified in their Judeophobia – the targets for their animosity were considered not only collectively responsible for the death of Christ, but also, as manifested in the Rothschilds, the profiteers of their misfortune. An attempt to escape capital’s domination in the person of Karl Marx led to another demonization: the Bolshevik revolutionary.

Reed fulfilled another circumscribed role: the entertainer. During this precarious period in his career he seemed to be communicating, with a kind of oblique defiance (via potent magical signifiers: imperial-religious sigils carved into his head; Nuremburgian staging), a familiar entrapment in a dangerous matrix of value exchange, of perceptual cul-de-sacs, feeding back repeatedly on themselves like the noise loops of Metal Machine Music. Re-imaging himself as Hitlerian ubermensch, he paid his parents and his manager back for their betrayal while embracing a symbol of total control, a decontextualized sigil to ward off ill fortune. It was also a strange, refractive, somnambulistic statement of Judaic pride. As literary theorist Michael Hardt has observed, in Jewish tradition the Golem is capable of running amok, but it is, at its core, a creation of love fashioned by kabbalistic wisdom. Reed was saying, I'll take your power symbols and make them subordinate to my art. I can do this because my people are survivors. We are spiritually duty-bound to be agents of change, despite the toll this duty extracts from us, because the world needs transformation as much as it needs order. And here in this arena of the imagination, one can capture codes, extract their surplus value, as well as be captured by them. One can be both subject and monarch in this regime of signs.

On the surface a glam cool simultaneously desexualised and hyper-sexualised with Cabaret-inspired Nazi chic, drug decadence reductio ad absurdum; underneath, an Oedipal drama exploded on a perverse field of intensity, of assemblages and becomings, for which rock music, Lou’s only god, was the plane of consistency. Caught between cold war blocs, how much were his 70s European audiences primed to subconsciously react to this symbolism? They belonged to a geographic community that had been beset by clarion calls of Zionist conspiracy from the established left and right - Communist authorities in Poland and Czechoslovakia, the Gaullist regime in France – as part of the propaganda arsenal used to dissuade public support for student revolutionary leaders: the same old divisive tricks given new coding. For English audiences, his stage design evoked a period of wartime history when many Britons equated Jews with Germans, just as the Germans were equating Jews with Bolsheviks, Social Democrats, exploitative capitalists, etc. Although it’s probably safe to say there wouldn’t have been a lot of anti-Semites at a Lou Reed concert, wasn’t magical thinking still a common trait of the time? Weren’t these Aquarian age audiences still attuned for occult significance, but for whom collectivist dreams were giving way to a new isolating particularism, with notions of identity under question? By drawing on totalitarian manifestations from the past, Lou Reed’s visual forms, aligned with music of oppressive volume, plugged into the energy of despotic signifiers floating loose in the contemporary atmosphere; impressions of an expansionist Soviet Union (another regime that employed psychiatry as a form of state repression), a capitalist United States imposing its will in Indochina.

With the dissolution of the ’68 student movement - an attempt, however inchoate, to steer a new democratic course beyond Communism and capitalism - rock arenas now provided cynosure for riotous affray. Sumner notes how the Free Trade Hall riot erupted after a single audience member threw a beer can into the drum kit, a signal for action detonating like a depth charge in a collective unconscious. Deleuze and Guattari understood well the kind of surreptitious power Reed could conjure in a rock concert, this merging of libidinal energy with subliminal paranoia: “The sign that refers to other signs is struck with a strange impotence and uncertainty, but mighty is the signifier that constitutes the chain.” Reed’s friend David Bowie put it another way in ‘Watch That Man’: “he acts like a jerk, but you know he’s only working the room. Must be in tune.” Reed’s assemblage of intensities, his insertion of himself as living symbol into a troubling historical continuum, signalled the love revolution’s failure left no way forward but the eternal recurrence of despotic codes and reaction against them. His refusal to do an encore was co-extensive with a whole chain of blockages – social, political, economic. In this emotional milieu, the concert hall, presided over by the performer as shaman and scapegoat in one, could seem not only a locus for the stimulation of desire but also a resented site of its containment.

The composition of affects he created in these concerts was to have an enduring influence: black clothes and shades, an effacement of personality he’d begun with the Velvets that would become goth formula with the likes of Sisters of Mercy frontman Andrew Eldritch; high contrast lighting that focused perception across smooth blackened space on this blank icon for a performer; the sepulchral ceremony of ‘Heroin’ refashioned into a narcotic drama of velocities and volumes, inspiring Joy Division in ‘Autosuggestion’ and the cyclical waves of steel that propel ‘Twenty Four Hours’, through them to The Pixies and Nirvana’s commercial formulation of the loud/soft rock dynamic. Finally, as though to reclaim this heritage of forms – hard rock, metal, punk – that he helped to inspire, Lulu, Reed’s controversial, but interesting, 2011 collaboration with Metallica.

Out of all those 70s audience members, Reed’s subcutaneous expression, his joyous negativity, may have spread its deepest roots in Ian Curtis, an English teenager consumed with the most dangerous romance of all – the poetry of despair. Tory voter and fan of the radical literature of William Burroughs and J. G. Ballard, Curtis also knew what it was like to be crushed between contradictory realities, in a double bind both historical and personal. Like many people in England at the time, Curtis seemed torn between the socialist compassion embodied in the welfare state and the media clamour of the winter of discontent, the demand for radical economic reform and the control of militant unionism. The sensitive young public servant who wrote 'She's Lost Control' about an epileptic girl for whom he found job placements and 'The Eternal' about a Down's Syndrome boy who lived in his neighbourhood when he was a child was also fascinated with the propaganda techniques of the Third Reich. Did the guilt he expressed when illness triggered his very own riot situation at Bury Derby Hall blend into a deeper unease over the direction in which his political choices were taking him, a world in which there was less room for the handicapped? (‘I guess you were right when we talked in the heat/There’s no room for the weak’ – ‘Day of the Lords’)

Joy Division's television performances take place on studio stages in which Curtis, like Reed, is an isolated figure, a one-man theatre of cruelty; his spatial separation from fellow band members a visual analogue for the vortex of personal difficulties that drew him further into the claustrophobic realm of his own songs. There’s a motion Curtis makes on a performance of 'She's Lost Control' filmed live in-studio for the program Something Else that seems to enact that archetype of nightmare where the dreamer runs in air like quicksand from some malevolent force. His defocused blue eyes drill into the camera with a crazed lucidity, filled with humility and rage, like the actor Martin Sheen (whom Curtis resembles with his militaristic haircut) in the opening scenes of Apocalypse Now. As Touch label boss Jon Wozencroft observes in Grant Gee’s documentary Joy Division, of all the figures in the post-punk scene, Curtis seemed to be the one who was most ‘destabilised’ by ‘the whole matrix of things’ going on around him. Its in that context that the Sisyphean gesture acquires a threatening polyvalence, evoking the hollow promises of enterprise culture for the structurally disadvantaged, the culture of surveillance disguised as entertainment, the eternal return of degraded simulacra. His performances generated their own dialectic of origin and reproduction: where did delirious fugue state end and medical condition begin? Did they simply coexist or was one the product of the other? Curtis provided more than a visual counterpart to Joy Division's music: he made of his body a cipher through which expression could be given to the geometry of anguish.

A culture irradiated with a romance of despair, a field of intensity transcending borders both geographical and stylistic, produced this biopolitical semiosis of divided selves. The counterculture's civil rights agenda continued with micropolitical refinement during this decade – feminism, gay liberation, black pride and other anti-racist movements, environmentalism (with its extension of rights to the natural world); all gradually becoming an accepted part of social discourse (at least until the conservative backlash against political correctness/woke ideology, the rampant spread of climate change denialism). World-transformative praxis was either lost in the blind alley of violence practiced by the Red Brigades or channeled into a critique whose hysterical nihilism and decadence camouflaged a collective need to examine those elements of the human condition that failed the revolution. There was a need for wholeness and balance that went beyond the pleasures of a hallucinogenic aesthetic, the radial symmetry of the mandala or the prismatic color of an LSD vision. Hauntological electronica at its finest – e.g., The Advisory Circle’s ‘Further Starry Wisdom’ - evokes this mixture of melancholia and hope more than it does retro-occult kitsch. Even artists as cynical of the hippie dream, as solipsistic in their pursuits as Reed or his nemesis/idol Frank Zappa, were still committed to the modernist idealism that underpinned countercultural aspirations. For Antonio Negri, the calls for radical democracy by the student revolutionary movements that had their moment in 1968, encapsulated in the Students for a Democratic Society’s Port Huron Statement or Rudi Dutschke’s demands for a more socially engaged religiosity, constituted a decisive moment of kairos, the ancient Greek philosophers’ term for a dialogue that once opened, cannot be silenced. An emerging ontology has been striving ever since towards expression, its materialization haunted by the fear of what might fill its absence.

A contrast in thematic emphasis between The Beatles' 'All You Need Is Love' and John Lennon's 1973 song 'Mind Games' is a compelling barometer for the cultural shift between the 1960s and the 1970s. Love is no longer a resource given out as freely as air as in The Beatles' sing-along favourite; now, it’s the answer to a human problem, but one that must be practiced surreptitiously, in guerrilla mode, as the voices of cynicism and complacency contain it within the boundaries of capitalist subsumption, aiming for a horizon of promise the music’s wistful circularity describes as chimera.

For continental philosophers of the post-68 period, the focus wasn’t love, but desire, an altogether more slippery domain. Negri, who was imprisoned in Italy for a time under false charges he was the leader of Brigate Rosse, returned to the medieval Dutch-Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza, an influence on Marx, Nietzsche and Freud, to recapture the vitality of revolutionary desire as the corrupted version of the Marxist program began to collapse around him. Spinoza's visionary concept of the unconscious as subject to, and product of, a matrix of infinitely extensive, spatiotemporal affects – his immanent conception of nature as singular substance divided into multiple attributes; pantheism without deities - was also important to Deleuze and Guattari. For them desire was a powerful, productive force within a transcendental unconscious, but not inherently good or bad: a concourse of existential modes capable of liberationist and fascistic tendencies, the body pursuing its capacities to affect and be affected. The paranoiac's urge to control, his groping amongst phenomena for material justification of prejudice and resentment, is the alternate current of the empath's focus on emotional connection. For Spinoza, humans must escape the imprisonment of these ‘sad passions’ and reach a greater awareness through the active search for reason of our role in the universe as monistic Substance: its existence within us as we exist within it, to paraphrase Michael Moorcock. His political formulation for this breakthrough, as further interpreted by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, was absolute democracy: finding the safest, most expressive outlet for conatus, or self-empowerment, by decentering and universalizing it. What they see as so subversive in Spinoza’s thought is the coexistence of an acceptance of necessity, in manifestations either good or evil, and the presentation of a goal – absolute democracy – that can only inspire the struggle for transformation. There’s a paradox in the human vortex: a regenerative void, as Negri defines kairos.

In experimental novels like The Atrocity Exhibition, Ballard portrayed the lack of this balance of forces as an absent cause of psychopathology in the late twentieth century; his elliptical, elusive work an examination of the interaction of the human psyche with the geometry of affects, an externalized psychotic landscape that conflates sexualized advertising and the atomic bomb, celebrity iconography with the atrocities of the Vietnam War; that sees a diagram for murder in the planes of a beautiful woman’s face, the inseparability of a cliff and a spinal column. The overriding focus of Ballard’s entire oeuvre, an ongoing surrealist manifesto, has not been the death of human feeling, but rather the elucidation of its evolutionary mutation into a radical connectivity, an immanent sublime unfolding in the interstices of dream and reality. As in Spinoza’s philosophy, there’s an attempt to reconcile man and nature by the same universal laws, to transcend the disharmony created by the imposition of artificial ones.

You need go no further for musical examples of the polarities of connective desire in the 1970s – furtive utopian urge and psychotic nightmare, like opposing sides of an exposed nerve – than the two songs that elevate Reed's 1975 album Coney Island Baby. The title track, a ballad afloat on zephyrs of doo-wop harmony and urban blues guitar, is a bittersweet celebration of misfits finding love in a hostile milieu. Like many great love songs, its spiritual intensity rests on contradiction, the transformative power of emotional connection both within and forever out of reach. The ominous 'Kicks’ on the other hand, a dialogue between homosexual thrill killers, hardens the soft-focus after-hours shuffle of 'Walk on the Wild Side' into febrile jazz-rock; steeped in a mood of crepuscular degeneracy, a mix gradually diffused by a tolling bell of guitar harmonics, submerged and influential like a decentred aura of evil.

‘Kicks’ resonates like a calculated affront in Reed’s repertoire. At first, it appears to be part of that ongoing agenda of negation and alienation, apotheosized for many critics in what they heard as the anti-musical statement of Metal Machine Music, that saw Reed’s apparent rejection of his own fans; an attempt to derail the momentum of gay liberation ridden by Transformer, dangerously playing into conservative assessments of homosexuality as not only deviance, but derangement. It’s really more of a political statement on what happens to sexuality in a culture (both gay and straight) predicated on the worship of power, the act of murder as the ‘final thing to do’ in the hedonistic pursuit of pleasure. The transformation of punishment into pleasure becomes a means of resisting repression by incorporating its means, but at some point dominant codes (religious, legal or consumerist) subvert these tendrils of liberatory investment into a desire for the subject’s own repression. How readily does sado-masochistic fantasy infiltrate the dreams of a subculture that has been on the receiving end of violent proscription since the socius first inscribed the great taboos? How many fathers defied, but gradually deified by unconscious proxy, assimilated and imitated? Like William Friedkin's controversial and misunderstood film Cruising, 'Kicks' examines an age-old poison of toxic masculinity that transcends boundaries of sexual preference.

A kind of bleak triumph forms the magical expression for the liminal zone where paranoia and fatalism meet covert utopianism in the 70s. It's a quality apparent at both the mainstream and underground levels, in lyrical concepts and the atmospheres of instrumental music. Words and music are both systems of signification capable of expressing the polarities, sometimes the coexistence, of the paranoid reactionary and the schizoid revolutionary. The uncanny power and timeless significance of art from this time is that you can never be completely sure from which end of the spectrum it’s coming.

Roger Waters' lyrics to Pink Floyd's 'Sheep' encapsulate the futile dead end that revolutionary violence had become by the tail end of the 70s with as much oppressive poignancy as the closed sequencer circuit of Heldon’s ‘Baader Meinhof Blues’, a minimalist, proto-Techno depiction of desiring machines locked in self-destructive orbit, while still imparting a sense of the historical necessity of this violence. Its outro chord progression, Status Quo’s rock ‘n’ roll revivalist clichés transmuted into acidic gold (as potent a condensation of punk’s back-to-basics approach, both reactionary and revolutionary as Simon Reynolds has argued, as anything in punk itself), describes the march towards a glorious sunset: part sad mirage, part enduring hope; gradually fading into the sounds of an nondescript countryside, its soil fed by the blood of all the other crushed European peasant revolts. For all the revolutionary opprobrium heaped on Floyd in the punk era, the musical world of Animals is really not that far apart from Joy Division’s: a progressive rock of technical simplicity and emotional depth, translucent production and programmatic concrète elements; pessimistic views of near-totalitarian societies on the verge of chaos. Bassist Peter Hook recognized the connection when he complained that Martin Hannett had made Unknown Pleasures sound like Pink Floyd (for Curtis it was Genesis that provided the disfavoured point of comparison for Joy Division’s final album Closer), before finally coming to the realization that the producer’s strategy made the album ‘timeless.’ Closer was even recorded in Floyd’s Britannia Row studios, the bastions of stadium rock bombast recognized by Sumner for their superior sonic technology.

A similarity of attitude as well as musical style can be discerned when Spacemen 3 reference the two-chord rock fundamentalism of Faust’s 'Krautrock' on a power mantra called ‘Revolution’, just as the German group's combination of utopian stance with dystopian moods is there in a neo-prog dirge like ‘There, There’ from Radiohead’s Hail to the Thief. The title may have been sarcastic, but as David Stubbs has suggested the space rock epic ‘Krautrock’ has the quality of an instrumental anthem for its titular scene, informed by both the electro-Teutonic avant-garde of Karlheinz Stockhausen and the American example of the Velvet Underground. Maybe the influence was reciprocal: Reed's sinuous, melancholic fuzz-sustain guitar work in his Metal Machine Trio seems to graft the Velvets’ ‘What Goes On’ tone with Steven Wray Lobdell’s sonic drill contributions to Ravvivando-era Faust.

A symphonic noise precursor to Metal Machine Music, the melodic beauty of ‘Krautrock’ is more than intermittent traces within feedback strata like the tangled skeins of an action hologram. Its will surging through a stellar dynamo of shrieking static and signal rupture, finally expiring in an ambience of indefinable loss and passing grandeur, a prescient echo of 'Twenty Four Hours' decaying radiance. A bass pulsates like an amniotic heartbeat but the noise brings to mind that spectral heliogram that returns as a focus of obsession in The Atrocity Exhibition, calling through a transcendental unconscious to our more distant biochemical origins in stars. A noumenal cosmology reverberates through Ballard’s novel, paralleled in the imaginative ambition of 70s space rock, that aims at surpassing all connective limits: one of the characters tells a woman she’s caught a star in her womb, while another provides concrete metaphor for impossible desire, perceiving in quasars ‘sections of his brain reborn in the island galaxies.’ ‘Krautrock’ raises questions of deep ontology as you listen to it: which is the greater violence, the thermodynamic vitality of the star or the entropic void that will eventually replace all its kind? The phenomenology of noise, a genre Metal Machine Music did so much to define, remains up for grabs: for some feminist artists, like Pharmakon, music’s ultimate oppressive embodiment; for others, its pure deliquescence and deterritorialisation, the fracturing of organized sound into desiring lines of flight.

There’s an abundance of desolate triumph in German experimental free rock, a mind-expansionary signifiance of deep ambiguity, conjured in collective improvisation filtered through production tools like echo, phasing and extreme stereo panning. For some of these groups, fired up by the revolutionary activism of their political counterparts among German post-war youth, pushing forward to the future meant first purging the nightmare of the past. It’s a spirit exemplified in that vertiginous transition in the Cosmic Jokers’ lysergic space rock jam ‘Galactic Joke’ when proto-New Age of Earth reverie becomes iron determination, a phaser-dub ferris wheel of spiral arms transformed by the mass of collective resolve into rotary scythes. A synthesizer line ascending a scalar staircase swathed in Wagnerian glory, drums battering at invisible boundaries with punk monomania. The apocalyptic ecstasy of the closing section of Can’s ‘Peking O’ from their 1971 masterpiece Tago Mago sounds even closer to the spirit of ’68 in sound – the will to power emerging in an ideological void; vocalist Damo Suzuki’s fugal glossolalia, Holger Czukay’s pulsating bass and the vast, echo-clatter of Jaki Liebezeit’s drums, the deconstructive noise of Michael Karoli’s guitar and malevolent clouds of Irmin Schmidt’s organ chords, participants in an occult ceremony conjuring wormholes to a constellation of transfigured values. The beautiful anger of Miles Davis’ psychedelic fusion epics like Get Up With It’s Mozambique freedom fighter tribute ‘Calypso Frelimo’ is the African-American parallel for Kosmiche as blocked praxis sublimated in the aesthetic unconscious; there’s a similar suggestion of a soundtrack to the Black Panther revolution that never happened in On The Corner and Dark Magus where the emotional core of blues provides centrifugal momentum to a sonic whirlpool of pan-global experimentation. Possible musical futures, by turns promising and scary, surveyed by deep avant-funk groove, ethnic drones and dissonant electronics.

This sense of bleak triumph in the seventies is also an animating impulse for a group like Hawkwind, for whom space travel is a biological and social imperative, for all their future nightmare of sonic attacks and black corridors, of betrayed warriors at the edge of time; historical futilities and antinomies unresolved and projected into the stars. It was in a songwriter like Peter Hammill whose obsessive examinations of time, consciousness and death suggest an attempt to produce a series of psychic axioms as rigorous as Spinoza's. It was in Francis Coppola’s cinematic vision of the Vietnam War, released at the end of the decade and set in the previous decade's year of the Manson murders when revolutionary ferment was becoming increasingly fractious and counter-productive. Not so much an anti-war statement as a meditation on power as universal condition. A final glimpse of redemptive hope, of the positive energy of empathy, is framed within darkness: a backwards glance at a forlorn hope.

The romance of despair was more than mourning work for sixties idealism, just as the prevalence of the dystopian in seventies popular culture was more than cautionary assessment of remaining paths, probing the outlines of an imagined future where love no longer existed at all. The dialectical knot of freedom and power may have seemed intractable - an unattainable feat of the collective imagination to see anything but a frightening anarchic void after the removal of corruptible organs of representation - but there was a strange, unplaceable energy nonetheless amid the malaise. The failure of the revolution of love was occasion for negative joy: egoistic impulses can always betray our capacity for kindness, but the contrasting drives are always inseparable, the result of the same geometric dance of interacting bodies and forces with the ability to either cooperate to form stronger valences or dissolve into separate atoms, allowing themselves to be subsumed under dominant codes. An appreciation that the ‘dynamic force of life’ is the product of ‘absolute immanence’, as Negri argues; that absolute democracy – no matter how often it is betrayed or how rigorously it is kept at bay by those commanding protocols – is the only true political corollary of this natural state. An impossible dream as close as the person standing next to you. It lives in some form in the Occupy/Blockupy movements and the hopeful beginnings of the Arab Spring: transformative, non-hierarchical forces facilitated by social media and the rhizomatic space of the internet.

The interface of the unconscious and reality described by Deleuze and Guattari may be like a machine, but it’s a soft one – capable of re-engineering itself to suit changing circumstances and opportunities. In the 70s, it allowed for the creation of a cult(ure) that made a means and an end out of despair: one that, if the acolyte allowed its seduction to do its work, would allow insights that could heal as well as depress. Despair became a radiant principle because, as Kierkegaard saw, of its paradox: as a product of the spirit that touches the eternal, it’s the condition that isolates us all, but also truly unites us, the only path of oneness. A vibrant plane of immanence: one where love could be something more than a transitory shadow cast in the geometry of affects.

The youth movements of the sixties put love forward as an absolute value thinking it natural and unassailable – it was, after all, supposed to be the foundation of Judeo-Christian ethics - but it was made counterintuitive by a matrix of conflicting values that remained when the revolution found its limits. After the tide of collective will Hunter S. Thompson described in his 1971 novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas receded, revolutionary tactics were still being worked for all their aesthetic possibilities. For songwriters like Reed and Curtis, gazing into primordial moral flux, good and evil inseparable and indissoluble, was a more fruitful path towards understanding than the constraints of a conventional morality that appalled them for its hypocrisy. For Deleuze and Guattari, the only way forward was in first confronting the fascist within. The hideous primal scene they describe – a triangle of affects in tribal torture whereby the concepts of debt and obligation, of desire and lack, are inscribed on the human body, overseen by the pleasure-seeking surveillant eye – is at the core of the semiotic chain that underlies all perversion and spiritual decay: the face of the paranoid despot underneath all the representations of Oedipus. How to define success in rooting out inner fascism when left spinning in the matrix of affect?

Existential loneliness and the truth of Friedrich Nietzsche's schizoid declaration - “I am every name in history” (the ones that call to Curtis’ protagonist through his dreams in ‘Dead Souls’) – are likewise commensurable; becoming as impulse a product of emotional dissonance, the conflicting needs for individuality and multiplicity. The delirium Deleuze and Guattari perceive at the core of capitalist society has its fluctuations as does the concept of Primal Oneness that Nietzsche alludes to in his Birth of Tragedy. The ‘great biocosmic memory’ that had to be overcome for state and economic paradigms to come into existence formed the plane of immanence from which the Greeks conceived tragedy as dramatic form, a tragedy whose chief origin is the suffering caused by individuation. Ian Curtis’ friend Genesis P. Orridge has spoken of their common relationship with their audiences as ‘camouflage’ for the expression of their individual negative joys. Live performance was an opportunity, desired and dreaded, to create a collective plateau of intensities, a body without organs, a liminal space between subjectivity and multitude. There were always dangers as those Deleuze and Guattari saw in trying to deterritorialize too quickly, at either the individual or collective level – fascism, terrorism, suicide. But there’s also opportunity to be the conduit of mass energies, facilitated by music’s mutability.

Lines of flight seem mostly closed off in Curtis’ lyrics, reterritorialised, the perspective of young men looking for a way out, but who, like the doomed acolyte in Kafka’s ‘The Judgement’, have the doors for their wandering slammed in their faces. We hear these lyrics through the spectral prism of reverberant production in shifting superimposition: warning transmissions from the Urstaat looming on either side of history, or the ecstatic outcries of a virtual present, filled with both danger and potential.

There’s one crucial moment of ambiguity, where a songwriter’s loneliness meets the energy of a musical collectivity. The persistent refrain of the “spirit, new sensation” in ‘Disorder’, a title that combines individual psychiatric condition and anomic milieu: does it refer to an apparatus of capture, like that confluence of reification and consumer fascism that Ballard made the focus of his final satirical trilogy of middle-class revolt? Or an imminent breakthrough into immanent desire? The tyranny of the transcendental signifier - those ‘prisons of the cross’ that Curtis explores in ‘Wilderness’, adopting the Burroughsian perspective of the hallucinating time traveller; broken apart by an abstract machine to free crucial modes of survival – community, compassion, cooperation – from a dogmatic cage. It’s the ambiguity of “spirit, new sensation”, how the separation of ‘feeling’ from ‘spirit’ inspires such desperation in the singer, that continues to resonate in British pop culture, just as another of the song’s Ballardian tropes did when it reappeared a decade later in ‘Made of Stone’ from The Stone Roses’ debut album. The destroyed car that inspires utopian fantasy for the isolated subject: symbol of the breakdown of civic order, iconography of rebellion – the coruscating afterimage of May ‘68, floating loose in time until it can crystallize in a new space.

Copyright © by Jonathon Kromka 2021

Comments

Post a Comment